Ronnie Spector's Memoir 'Be My Baby' is the Bad Girls Bible

Highlights from the 1990 tell-all by the lead singer of the Ronettes, presented by T. Bloom

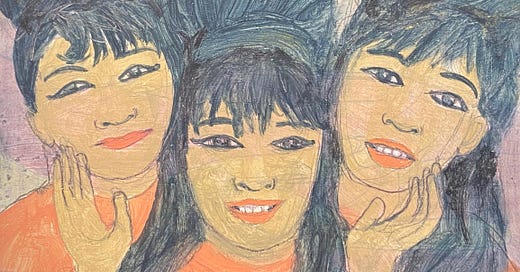

[Main image: painting by Jordan Buschur]

The outpouring of love and grief over the death of Ronnie Spector this month has been wondrous to behold. As a ‘60s girl group pioneer, she survived an era of entertainment in which women were considered even more disposable and replaceable than they are now.

The list of incidents she survived is actually so long, it seems miraculous that she lived to be 78, finally passing after what her family described as a brief battle with cancer. She survived growing up poor in Spanish Harlem; she survived being married to monstrous music producer Phil Spector; subsequently, she survived a lengthy struggle with alcohol abuse. She survived fame, as well as the long fallow periods when it felt like the sun had set on her career — which was largely Phil’s doing.

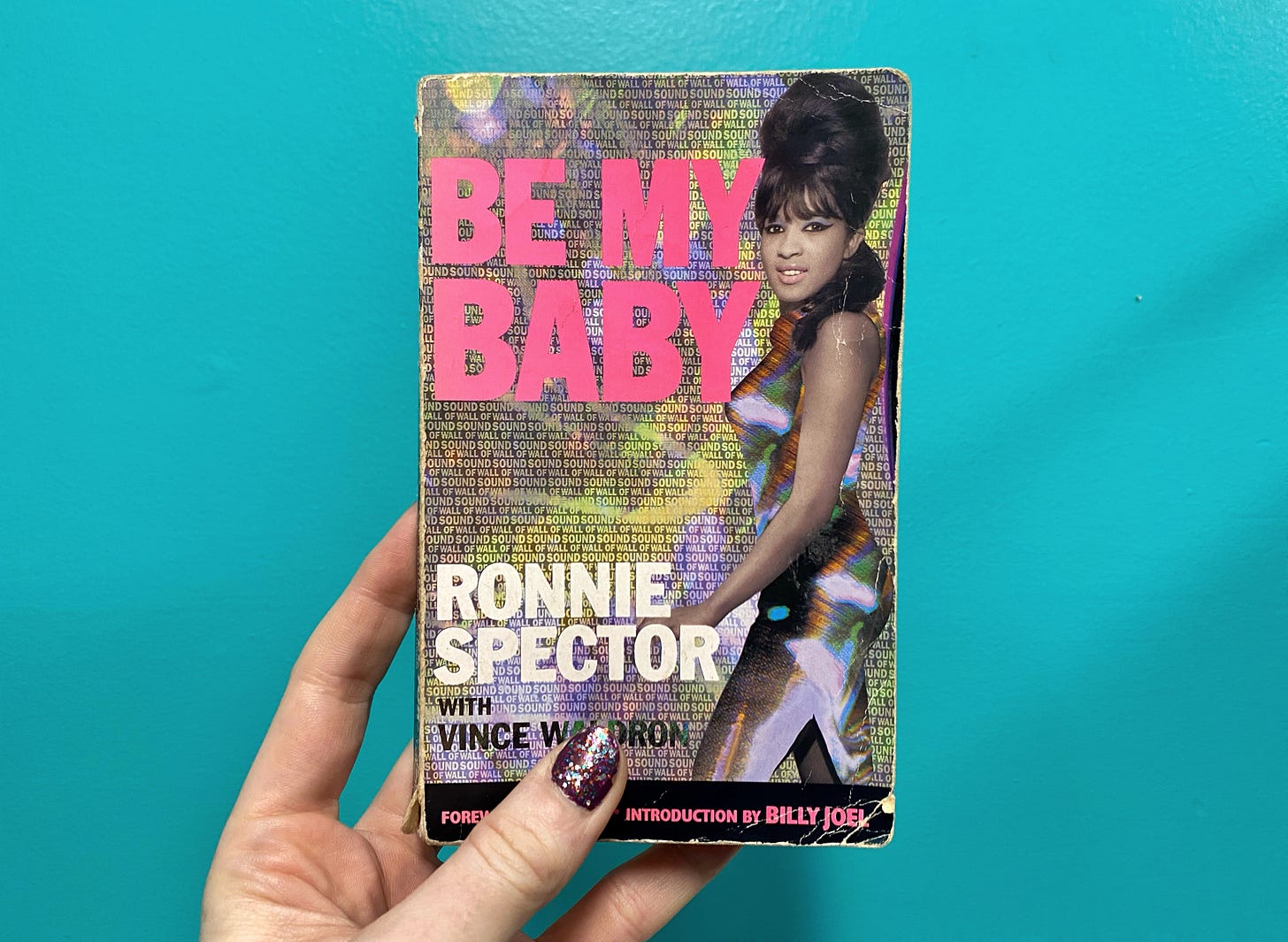

She even survived a brief stint as a writer, which can be harder than it sounds. In 1990 the memoir Be My Baby: How I Survived Mascara, Miniskirts, and Madness was published by Pan Books, accompanied by a foreword written by Cher and an introduction by Billy Joel — bolstering her credibility against any claim that she was out to make a quick, slanderous buck.

Survival is a theme here as well. Cher writes: “Ronnie went through some tough times, but the important thing is she survived and she’s still around to tell the tale.” Inside the cover is a blurb from the style magazine The Face: “Ronnie survived, and by the end of her book you sense that the strength she projected onstage was not, after all, illusory.”

She survived... She survived... She survived…

This became the narrative surrounding her life story, but all she’d ever wanted to do was sing. So what happened?

I’ve written before about the ephemeral nature of pre-Internet memoirs. For the most part they could be counted on to pop like a firework, causing a brief sensation before quickly fading out of print, making them harder to revisit as years went by. It was an excellent medium for (in)famous women to express themselves candidly, sharing the kinds of biographical details no interviewer would ever dare ask, without being dogged by them in the longer term — not unlike the way future generations of Bad Girls would come to rely on Snapchat and other “vanishing message” platforms.

From what I can tell, Be My Baby (named after the Ronettes’ hit song, which sold two million copies in 1963) is currently out of print, although that’s likely to change if the A24 film adaptation starring Zendaya ever gets off the ground — or perhaps even as a result of Ronnie’s death, which is sure to renew interest in her incredible life story and body of work. But for now, since this incredible book remains relatively difficult to access, I’m happy to throw you some highlights.

Ronnie’s writing voice is as raw and candid as one might expect from hearing her sing, bursting with personality and wit. Here are some excerpts from the early chapters:

The book’s opening line:

“Skinny Yellow Horse. That was the name the black kids had for me when I was growing up, because I had light skin and I was so small that I’d always kick like a little pony whenever I got into a fight. And I was always getting beat up.”

On growing up in Spanish Harlem:

“Junkies! Someone was always talking about junkies when I was growing up. I never saw one, but boy, did I want to! I would cringe getting my polio vaccination, but for some reason I was fascinated by the idea of these people who stuck a needle in their arm every day. I couldn’t wait to lay eyes on someone who did that. One day my cousin Mae spotted a junkie outside my grandmother’s house. ‘Hey, look out the window,’ she said. ‘It’s a junkie.’ I jumped up from the couch and ran toward the window but my grandmother stopped me halfway. ‘Don’t you go over to that window, Ronnie,’ she commanded. ‘You don’t need to be looking at no dope addict.’ That just killed me, because all I wanted was to see what a real junkie looked like. But it was forbidden. I never did get to see a dope fiend, unless you count Frankie Lymon.”

On sneaking into the Peppermint Lounge to perform:

“Since Nedra and I were still underage, we practically needed to disguise ourselves to get past the doorman. That’s where having six aunts helped, because they taught us all the tricks to using eyeliner, blusher, and lipstick. It’s funny, but as protective as they were in most ways, Mom and my aunts didn’t seem to mind grooming us to get through the doors of New York’s steamiest nightclub… My mother even gave us Kleenex to stuff in our bras before we squeezed ourselves into three matching yellow dresses with taffeta and ruffles coming down the front. Then we teased our hairdos until they were stacked up to the ceiling.”

On the Ronettes’ Bad Girl image:

“When the audience started responding to our street look, we played along. The songs we sang were already tougher than the stuff the other groups did. While the Shirelles sang about their ‘Soldier Boy,’ we were telling the guys, ‘Turn on Your Love Light.’ That was our gimmick. When we saw the Shirelles walk onstage with their wide party dresses, we went in the opposite direction and squeezed our bodies into the tightest skirts we could find. Then we’d get out onstage and hike them up to show our legs even more. After a while it got to be so much trouble hiking these tight skirts up that we finally just cut slits up the sides. That was the Ronettes’ look.”

Backstage gossip:

“[Dusty Springfield] shared a dressing room with us once, and I never saw anyone get so frustrated backstage. She hated being stuck back there all day and night, and she expressed her frustration with dishes… When Dusty Springfield got upset, she would go out to the hallway and throw cups and saucers at the stage door. By the second show you had to step over piles of broken china just to get to the stage. After she broke every dish in the place, she’d send her valet out to Lamston’s five-and-ten-cent store to buy more. This poor guy would come back with whole boxes of white cups and saucers to throw at the exit door. She’d break dishes for five minutes, then she’d walk back into the dressing room with a big smile on her face. I guess it helped her relieve tension, but we all thought she was nuts.”

So how’d they end up getting the legendary Phil Spector’s attention? According to Ronnie, she and the girls (sister Estelle Bennett and cousin Nedra Talley) simply looked up his record label in the phone book and called the number, asking to speak to him. Somehow it worked: they were connected by a receptionist, and Spector invited the Ronettes to meet him in the studio. “All we did that whole day was joke about which one of us was going to marry this millionaire,” Ronnie writes. But before that fateful day would come, the Ronettes became an overnight sensation. Touring and partying with The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, exposed the girls to stardom (and debauchery) beyond their wildest imagination.

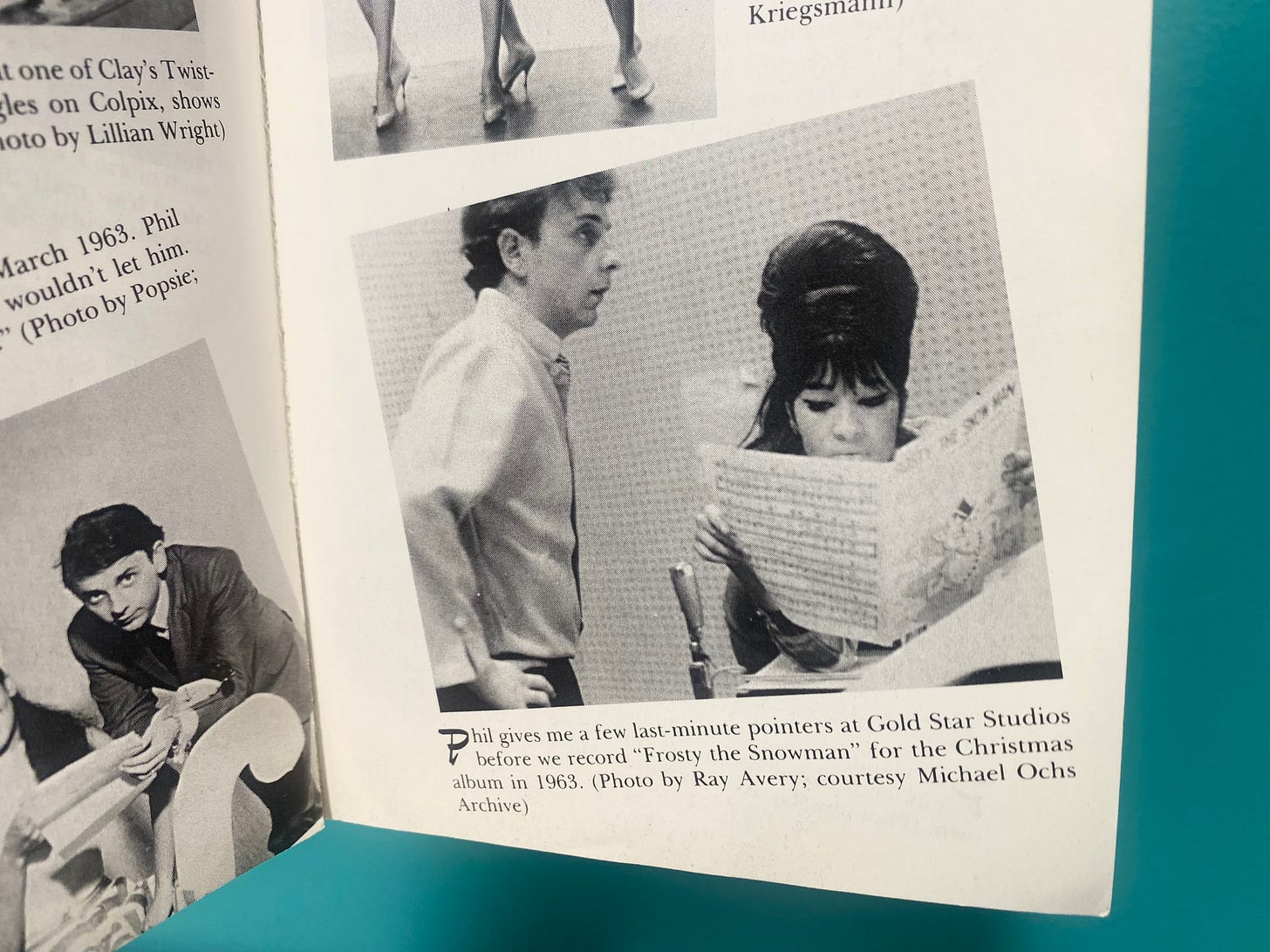

Phil’s presence looms over the much of the book. He was Ronnie’s first love, and he undeniably made her a star. However, the moment they became romantically involved he began to actively sabotage her career, understanding better than she did how performing would keep her band traveling in the company of other rock stars, beyond his control. So Phil kept her hard at work in the studio, constantly recording new songs which he’d then ultimately decline to release. And this gambit worked: the Ronettes’ lightning-strike moment faded, and Ronnie — now married and living far from her family — steadily lost contact with the outside world.

•

The abuses outlined in Be My Baby are so numerous and so preposterous, it’s impossible to do them justice with a handful of excerpts. Phil’s money, power, and paranoia were all channeled into keeping Ronnie bottled up inside his mansion. When he bought her a car, it came with an inflatable “Phil” to ride in the passenger seat whenever he wasn’t by her side. Once after Ronnie sprained an ankle on the stairs, Phil had his doctors immobilize her in a wheelchair with a full leg cast, leaving her under the supervision a nurse who kept her drugged day and night while he conducted business out of town.

As her health deteriorated due to drinking, occasional stays in a sanitarium began to feel almost like vacations: they were her only break from Phil’s obsessive oversight. After one such stay, she came home to discover that he’d already initiated adoption proceedings so he could surprise her with pair of twin boys for Christmas.

The story of Ronnie’s escape truly belongs in a film: she fled the Spector mansion barefoot (a plan devised because she was only allowed to stroll the grounds without shoes, as she was considered a flight risk) to a location down the street, where her mother was waiting to drive her directly to a divorce attorney’s office.

Ronnie doesn’t shy away from her life’s lurid details, even when it comes to her own regrettable behavior. Decades after the fact, she is capable of seeing herself for who she really was at the time: a young woman who’d gone straight from high school to superstardom to a life sentence in a million-dollar prison. Her immature exploits are recalled with a mordant humor that informs the reader how long she’s spent sitting back and learning from all this, and as a result she’s able to spotlight key details with laser precision.

This helps the book succeed beyond the scope of sizzling celeb tell-all, and also serves as another preemptive defense against claims that she was simply out to skewer her ex. In the early chapters, Ronnie puts painstaking effort into outlining what she loved about Phil, her sincere attraction to him, the thrills (as well as the chills) of their sex life. She didn’t have to recreate those moments for us — indeed, there are many readers who would probably prefer that she didn’t. But through her eyes, we’re able to appreciate what the hot young singer must have seen in the sensitive, balding, awkward, producer genius. At one point Ronnie recalls a friend asking if she really thought Phil was cute. “Yeah,” she replied, “Don’t you?” Speaking for virtually everyone, the friend replied: “Not the way you do, girl.”

And while Ronnie is very direct in pointing out the ways in which Phil ruined her career or even endangered her life, she’s still quick to give him credit for the decisions that launched her to stardom in the first place, especially in terms of defining the Ronettes’ iconic sound.

Here’s her account of the 1964 recording session for “Walking In The Rain”:

“When it came time for me to record, Phil said, ‘Go on into the studio, I’ve got a surprise for you.’ I stepped in and stood at my usual spot behind the music stand. ‘Okay Ronnie, just listen to this.’ I put the headphones on as Phil reached over to flip the tape on.

“Everything was quiet. Then all of a sudden I heard a low rumble, like there was thunder coming in from every corner of the room. It was the intro to the song, but Larry and Phil had mixed the sounds of a real thunderstorm in with this beautiful melody. It was absolutely perfect. I closed my eyes and I was in a whole other world.

“I started singing on the downbeat. I thought I’d just do a rough take to get a feel for the song before we recorded it. I was really into it, and I kept singing all the way through the whole song. When I finished, I opened my eyes and found myself standing in complete darkness.

‘What happened?’ I asked. I couldn’t see Phil or any of the other guys in the glass booth, and I started to wonder if they’d even heard my rehearsal take. Then Phil’s voice came out over the speaker.

“‘That’s the one,’ he said. ‘We can go home now.’

“‘You were recording that?’ I asked. Then I walked straight out of the book, feeling a little confused. ‘But that was just a rough one,’ I said. ‘Let me try it one more time, I know I can really feel it now.’

“‘Oh, you felt it,’ Phil said. ‘Listen for yourself. Play it back, Larry.’ And when I heard it played over the speakers, I had to agree with Phil. It was a perfect take. And that’s the take you hear on the record today.”

The first two-thirds of Be My Baby is a love story that flies off the rails; the chapters that follow leave Ronnie to confront the realities that await on the other side of love, wealth, and stardom. Her drinking problem is not magically solved by emancipation from Phil — especially since he’s able to use shared custody of their adopted son as an instrument of manipulation. Ronnie finds her way back to the stage and reconnects with the audience who fell in love with “Be My Baby,” but her tumultuous lifestyle keeps her from riding that wave to higher ground.

This is the phase where many Star Lady Memoirs start to lose steam, because they usher readers into a phase of the author’s life that is less familiar, less connected to the glittering image that most fans hold dear. Remarriages, family struggles, recovery attempts, small meaningful successes unrelated to their illustrious past — these subjects can be far less accessible, and the author’s close proximity to them can be a literary blind spot. Can a story as sensational as Be My Baby withstand the loss of its central villain?

Whether because of Ronnie’s own keen insight or the assistance of Vince Waldron (credited with helping to midwife her manuscript), these lower-wattage anecdotes still manage to ignite. In fact, one of the most memorable chapters describes a time when, in the depths of her despair after leaving Phil, our heroine accidentally burned off all of her hair in a terrifying cognac fire — a story she still tilts in an uplifting direction because of the wake-up call it provided in terms of her drinking.

“God let me burn my hair off,” Ronnie writes, “because it was the only way he could make me understand that everything grows back.”

•

Stardom often emerges as a path for those who never saw normalcy as an option. In the epilogue of her book, Ronnie writes:

“I still have to pinch myself sometimes when I see Jonathan and the kids wrestling in the yard or playing Candyland in the living room. I’ll ask myself ‘Am I in the real world? Or have I been drinking again?’

“But my life is not a dream. It may not be Ozzie and Harriet, but it’s real. I gave up alcohol eight years ago, before my first baby, and I’ve only recently started to accept as normal all the stuff most people take for granted — shopping for groceries, reading magazines, going to the PTA. In fact, I’ve gotten so normal that sometimes I look back on my old life and wonder if that wasn’t really the hallucination.”

Many young women who grow up in the margins make a point of transforming themselves into Bad Girls in order to kick and scratch their way out. Some of them may recognize the situational nature of their plight, and look forward to the other surprising transformations that no doubt await as part of their longer-term survival. Others have no concept of the long term, and circumstances conspire to put “normal” far beyond their imagination. Success can mean death (or worse) for a person like that. It’s a struggle that many young women in the music industry still face today, with outcomes that are scarcely different from Ronnie’s.

The fact that little Veronica Bennett set out down one path and found herself on quite another, and then yet another, is not particularly unusual — although it’s impressive that she managed to survive long enough to reflect it, and also lived to see her ex-husband face punishment for his brutality against women (Phil Spector died of Covid-related complications last January while serving time for the murder of actress Lana Clarkson).

It’s the fact that Ronnie managed to document this journey so faithfully that makes her quite unusual indeed, remaining visible (even in death) to future generations of Bad Girls as a product of her own hard-won “normalcy.” The conclusions she ultimately drew about life’s purpose were matched to her own personal needs, which had awakened in her over time; that is the winding course to redemption she seems to recommend to others who become lost in the dark.

“There are a lot of Phil Spectors out there, but not all of them keep their wives locked up in twenty-three-room mansions. You can just as easily be a prisoner in a Bronx tenement or a tract house in New Jersey. It’s not about being locked up in a house at all, really — but about being locked up in your heart. And no one can put a lock on your heart but you.”

Which is not to say we’re to blame for the harms other people choose to commit against us, nor are we solely responsible for extricating and healing ourselves. But I think Ronnie’s parting words are aimed at something essential to the Bad Girl spirit: the hidden confines of harness and independence, the false idea that one must live or die by the terms one has already committed to.

This is why a silver thread of vulnerability remains defiantly woven through the Bad Girl tapestry, streaming all the way from Ronnie’s time to the present day. The emphasis on one’s “ride or die” chosen family; the thirst for justice and the righting of wrongs; the need to feel special, to be supported and represented, even appearing onstage together in identical costumes. Bad Girls are forged in response to society’s most predatory impulses, and sadly may never know greater safety than in these fleeting moments onstage, singing and dancing in triplicate just out of the crowd’s reach. But what happens to them the moment they step off that stage?

Ronnie knew. “I don’t know anyone in the business who’s got the life I’ve got,” she wrote at the end of her book, over thirty years ago. “I just thank God I’ve made it this far.”

•

If you’ve enjoyed reading this free post, why not subscribe for more JUDGEMENT? Sign up to have free content delivered straight to your inbox, or pay $5 for regular *exclusive* content! Thank you for enduring this sales pitch.