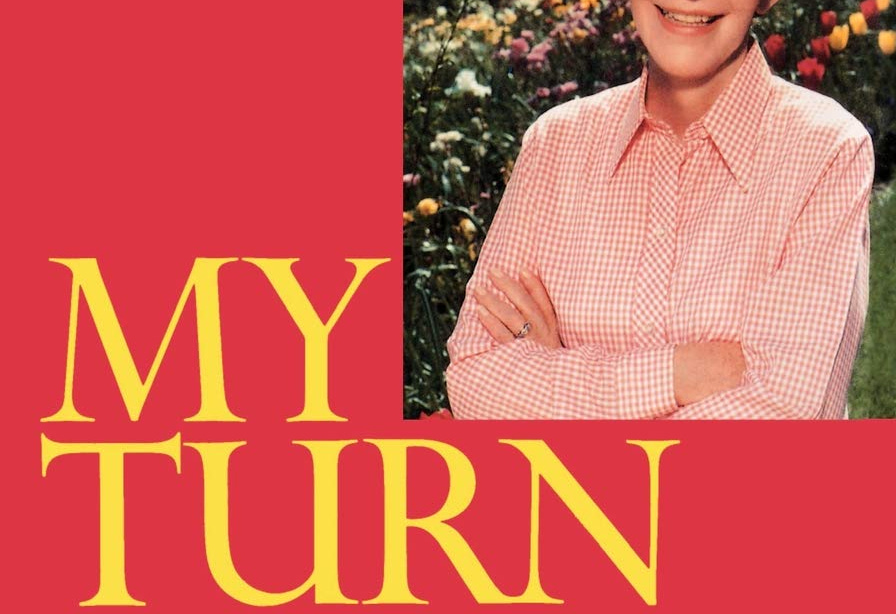

My Turn: Nancy Reagan and the Case of the Weaponized Memoir

T. Bloom exhumes portions of the notorious 1989 book written by a notoriously self-forgiving figure

[A version of this article was originally published by Penguin Random House in 2016]

Nancy Reagan may never have “started a national conversation about HIV/AIDS” (as Hillary Clinton apologized for erroneously claiming in 2016) but she did attempt to hold forth on a wide variety of issues during her tenure as First Lady and beyond, such as drug addiction — a topic she still remains humorously associated with today.

To her dismay, these conversations were often eclipsed by talk about the First Lady herself, whose incumbency was derailed early and often by scandal: her acceptance of free clothes from top designers, her (over)involvement in cabinet politics, her reliance on astrology to dictate Ronnie’s calendar, her difficult relationships with their children… the list goes on and on.

At the time, this blitz of bad PR was a fairly unprecedented situation for a FLOTUS. The public’s opinion of her direct predecessors had been neutral at worst; while the position has many responsibilities both diplomatic and domestic, most 20th-century First Ladies opted to keep a relatively low profile. But with Hollywood-sized ambitions to match her husband’s, Nancy recognized her potential to be remembered as another Eleanor Roosevelt or Jackie Kennedy. She leaped headfirst into the role, overconfident in the self-evidence of her charms and unprepared for the degree of media scrutiny that would follow (and the public support that wouldn’t).

In her eagerness to be embraced as an historic figure and person of substance, Nancy misread the zeitgeist from day one, co-presiding over the most expensive inaugural celebration in American history: $11 million spent on four days’ worth of gala events, which even Republican friends like Barry Goldwater deemed too ostentatious for a nation whose citizens were enduring severe economic recession.

It’s unsurprising that eight years later — having endured not just an attempt on her husband’s life, a mastectomy, and the death of both parents, but also that constant drubbing by the press — Nancy left the White House embittered and uncertain of her legacy. That much is indisputable, regardless of your political leanings, since she told us herself in a 1989 memoir bearing a deliciously retaliatory title: My Turn.

Ever since the aforementioned Roosevelt, there was plenty of precedent for a FLOTUS to be a woman of letters. Jackie Kennedy had firmly established herself as editor and essayist, and Rosalynn Carter ultimately wrote five books in total, beginning with First Lady From Plains in 1985. Later on, Ladies such as Clinton, Laura Bush, and Michelle Obama opted to kept their memoirs strictly inspirational, beckoning younger women into leadership and civic duty. Ever unable to consider the long term, Nancy Reagan stands virtually alone among them all, an author flagrantly determined to settle scores both personal and political.

In fact, this strategy of “damage in the form of damage control” is deployed on the first page, as My Turn opens with a dedication serving as a sort of “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here” signpost for Nancy’s family members:

To Ronnie, who always understood

And to my children, who I hope will understand

Likewise, the foreword gets right to the meat of it. “While Ronald Reagan was an extremely popular President, [I came to realize] some people didn’t like his wife very much,” Nancy writes. “Something about me, or the image people had of me, just seemed to rub them the wrong way.”

Anyone looking to mine dirt from the chapters that follow will find enough to warrant at least two shovels, and possibly the rental of premium construction equipment. However, Reagan is canny enough to know why you’re here. She’s all too happy to dole out the scandalous details, but she makes sure to organize her anecdotes so you’ll have to dig through plenty of humanizing pro-Nancy moments of genuine fear, heartbreak, and disappointment in order to get to them.

Take the very first chapter, “There’s Been a Shooting,” which hones in on John Hinckley Jr.’s assassination attempt — a mere sixty-nine days into Reagan’s Presidency — as an opportunity to reframe the reader’s perceptions of her in all the events which followed. “Looking back now,” she writes, “I see that I was in a state of shock for much longer than I realized, and that the psychological effects of March 30 were more enduring for me than they were for Ronnie.”

Consider it: at the time of the shooting, Nancy was a woman in her early sixties who had just moved cross-country following a year of rigorous campaigning. Her husband, ten years her senior, had been shot in the chest and nearly killed — an event recorded on video which replayed nonstop on TV news broadcasts. Regardless of whether it seems cynical to emphasize this crisis as an excuse for all the poor decision-making which followed (she is definitely doing), Reagan isn’t wrong. Few persons public or private could withstand a catastrophe of this scale, and few First Ladies have ever had to. One’s imagination wanders first to Jackie Kennedy (Reagan tastefully resists the temptation to draw this comparison herself, but probably wouldn’t have minded if someone else did), although a closer parallel is Edith Wilson, whose husband Woodrow was paralyzed and bedridden following a major stroke during his second term, forcing the FLOTUS to effectively govern in his stead for about five months.

So this is a compelling sort of apologia with which to open, and one that points directly to the lack of humanity and imagination in the American news media across the months and years that followed the shooting. At a time in life when most of her generation were retiring and winding down, Nancy found herself under unimaginable strain — but for the most part she was judged (both at the time, and by history) only on certain outward expressions of that trauma.

“I was so shaken by the events of that spring that it took me a couple of years just to say the word ‘shooting,'” she confides in My Turn. “For a long time I simply referred to it as ‘March 30,’ or, even more obliquely, as ‘the thing that happened to Ronnie.’ For me, the entire episode was, quite literally, unspeakable.”

In Nancy’s eyes, the disintegration of her FLOTUS image began shortly afterward, with a project which clearly was courting comparisons to Jackie Kennedy: a major renovation of the White House, funded by private donations. As in so many cases, hindsight proved 20/20.

“On television, reports of the renovation were contrasted with rising unemployment and homelessness… I was particularly hurt by a column by Judy Mann in the Washington Post, who write that instead of helping all Americans, ‘Nancy Reagan has used the position, her position, to improve the quality of life for those in the White House.'”

The next couple of chapters walk us through at least two other high-profile scandals: Nancy’s designer wardrobe, and her reliance (and Ronnie’s, by extension) upon the advice of astrologer Joan Quigley. In the case of the former, she doubles down:

“By the end of 1981 I had a higher disapproval rating than any other first lady of modern times,” she reflects, then pondering: “If the public really wants the first lady to look her best, why then was I attacked so strongly, and so often, for my wardrobe?” Her conclusion: “One reason may be that some women aren’t all that crazy about a woman who wears a size four, and who seems to have no trouble staying slim.”

Take that, America!

Nancy’s candor remains as double-edged as ever; even in print she’s still blithely unaware of how others might read between her hastily-written lines. “If you look back at some of my predecessors,” observes Nancy, “You’ll see that after a few months, even the first ladies who seemed not to care very much about fashion and appearance began to pay more attention to their hair and their clothing. As I write these words, this is happening to Barbara Bush.”

She’s probably not intentionally throwing shade here — the Bushes were practically family at that point, and it’s true, Barbara was not as image-conscious as her fancy friend. Leaving all that for the reader to determine, however, is classic Nancy. There’s an art to expressing oneself in ways that aren’t so open to interpretation, and it’s one she simply never mastered.

Feeling duly exonerated on the fashion front by a rehash of her self-effacing Gridiron Dinner performance of “Secondhand Rose,” which she clearly saw as a PR coup de grâce, Reagan moves on to the tougher topic of her astrology addiction. Regardless of whether one considers her a frivolous or insubstantial person, her defense of those phone calls with Quigley as a coping mechanism following Ronnie’s near-death experience seems legit. Unable to sleep or eat, Nancy claims she shed fifteen pounds from her already slight frame during the months following the shooting. Though she still considered the psychic a close friend at the time of this book’s printing, one could now make an argument that Quigley took advantage of a vulnerability — the two were put in touch by Merv Griffin after the astrologer claimed she could have predicted and ultimately prevented the attack. Post-disaster “predictions” are the kind of classic cheat that scam-artists like Sylvia Browne have based entire careers on.

“My relationship with Joan Quigley began as a crutch, one of several ways I tried to alleviate my anxiety about Ronnie,” Reagan confesses to us. “Within a year or two, it had become a habit, something I relied on a little less but didn’t see the need to change.” While the press attention was humiliating (the story broke via disgruntled former White House Chief of Staff Don Regan’s 1988 memoir For the Record: From Wall Street to Washington), Nancy admirably refuses to beat herself up about it. “What it boils down to is that each person has his own ways of coping with trauma and grief, with the pain of life, and astrology was one of mine,” she says. “Don’t criticize me, I wanted to say, until you have stood in my place. This helped me. Nobody was hurt by it — except, possibly, me.”

Hitting all of My Turn’s breathtaking highs and lows would require chapter-by-chapter analysis, and trust me, it’s an experience best enjoyed firsthand. Rest assured that somewhere between ZodiacGate and Iran-Contra, the former First Lady re-introduces the reader to the former Miss Davis, a young actress from a tumultuous showbiz family who sought the limelight (despite being personally warned away by Katharine Hepburn) and ultimately did claim a modest share of it. You can tell Nancy means these stories to have an endearing effect, and they do… if not always for the reason she intends. The more we learn about her background, the more inevitable all her political stumbles appear to be. Nothing in Nancy’s education or career could have prepared her for the kind of diplomatic challenges that laid in wait for her like tiger traps… but she’s also the one who foolishly rushed ahead, seemingly eager to tumble into them. This lack of introspection makes the book ring especially hollow as she ultimately asks the public for clemency, if not pity, offering herself up as a tragic figure instead of a contemptible one: someone who merely rose with the tide for years, never imagining she’d sink with it as well.

Did she really imagine that anyone outside of her immediate circle would find that relatable? Or that the Americans who’d suffered most at the hands of the Reagan administration would submit to reading an entire book about it?

Rising and sinking right alongside her were, of course, her children Patti and Ron and stepchildren (from Ron’s first wife Jane Wyman) Michael and Maureen. Even though Nancy is up-front about her failings as a mother in My Turn, she still can’t resist heaping parental guilt upon them, citing her relationship with Patti as “one of the most painful and disappointing aspects of my life,” and then airing humiliating details about her daughter’s teenage indiscretions that simply can’t ever be taken back. Ultimately Reagan exonerates herself from responsibility for this damage, as well as any yet unforeseen: “When your child has a difficult time, it’s only natural to blame yourself and think, What did I do wrong? But some children are just born a certain way, and there’s very little you can do about it.”

Upon the book’s release, The New York Times was having none of it, asserting that Nancy “loved every moment” of attention during her White House years, citing the book’s many instances of malicious laundry-airing as evidence of this. Eight years of Reagan overexposure had left the nation jaded and exhausted. “Does the country derive any real benefit from putting an essentially domestic relationship onto such a grand stage?” implored reviewer R.W. Apple — blissfully unaware of everything the Clinton years would bring.

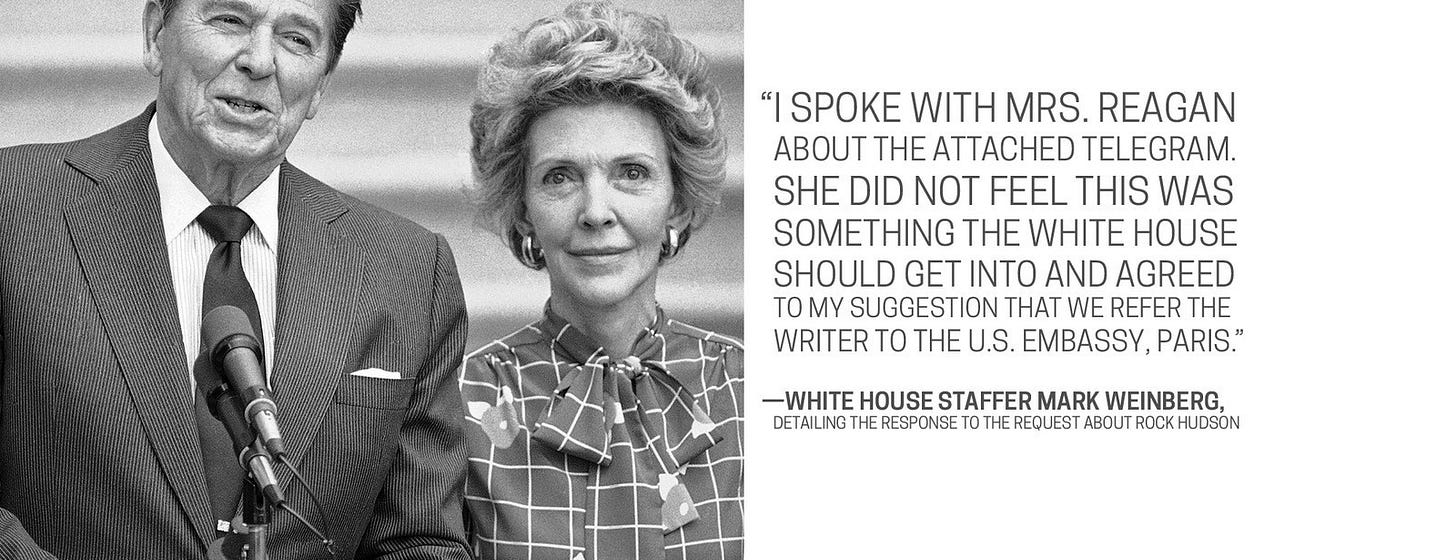

For the record, the subject of HIV/AIDS is avoided here just as it was throughout the rest of the Reagans’ tenure. The term doesn’t even warrant a mention in the book’s index, although Rock Hudson does, guiding the reader to a brief mention of the actor’s decline excerpted from the First Lady’s personal diary: “News came today that [Hudson] had lung cancer in Paris, so we called. But now there seems to be some question.” An aside is added:

[Later, of course, we learned that it was AIDS. He had been to a White House dinner and had been at my table. I remember sitting across from him and thinking, Gee, he’s thin. I asked if he had been dieting, and he said he had been hard at work on a new picture and had lost weight.]

Nancy presents this as one of her classic foot-in-mouth moments, which she includes in the spirit of self-deprecation — not realizing that everything she left unsaid would speak so much louder.

That, too, is classic Nancy.

[graphic via Buzzfeed]

As difficult as she was to embrace, it was downright dangerous to underestimate her. Paul Slansky’s obsessive critique of the Reagan years, The Clothes Have No Emperor, opened with a quote unearthed from a 1939 high school yearbook praising a certain teenaged leading lady: “Nancy knows not only her own lines, but everybody else’s. She picks up the cue her terrified classmates forget to give, improvises speeches for all and sundry. Just a part of the game for Nancy.”

The play? George S. Kaufman’s First Lady, about a woman determined to elevate her own status by getting her husband elected. Forty-odd years later, when the same actress was caught on microphone feeding lines to her stymied husband, the reviews weren’t so warm.

When so many of one’s life events — whether good or ill — seem to be written in stardust, it might be reckless to proceed without an astrologer. All the same, Nancy did eventually appear to learn some important lessons which had yet to crystallize during the writing of My Turn. Taking care of her husband as he further succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease demanded the former First Lady’s full attention, and following his death in 2004 she continued to relax into the relative privacy of civilian life, keeping the spotlight trained on public works in Ronnie’s name.

Unlike the Bushes and Clintons — battle-tested political dynasties whose members have proudly, eagerly borne their standards into the new millennium, for better or worse — the Reagans have remained an relatively understated presence ever since. At the time of Nancy’s death in 2016, she enjoyed much closer relationships with all her surviving children (Maureen lost her life to cancer in 2001) than during those traumatic White House years.

Today My Turn reads like an artifact of a truly bygone political era. Back then, books went easily in and out of print all the time; you could flash a stiletto at enemies and be assured the glint would eventually fade. Barbara Bush was the very last First Lady to enjoy this luxury, though she endured fewer enemies and tragedies than Nancy (and possessed far more restraint). As a result, even with that raw, unpolished quality she was famous for, Barb’s two memoirs are extremely boring and uneventful in comparison. Since then, the impact of the internet age on FLOTUS writing styles has been quite striking: since these works are guaranteed Rosetta Stone-caliber permanence, every sentence must be carefully screened for the impact it may have on their friends, family, and historic legacy.

The shadow of My Turn must have also loomed over these later authors as they wrote, informing the tone and ultimate purpose of their work. While Nancy’s book may have humanized her somewhat, it would be hard to argue that it redeemed her. Its author was a vain, sensitive woman who spent her lifetime seeking approval from ever-larger audiences, and unfortunately her main contribution to literature, as well as American history, is an account of how much it hurt to be denied that approval.

This makes My Turn the kind of failure it’s impossible derive too much joy from, no matter how much contempt you might have for its nakedly contemptible narrator — although, as is the case in most human tragedies, it remains impossible to look away. And of course, that hook was skillfully embedded into the book’s very purpose. One could say that by 1989, it was the only real power she had left. Forced to abandon her fantasies of being celebrated in her twilight years, Nancy settled for trying to be seen for what she truly felt she was: neither very good, nor very bad. No kindly grandmother-type, perhaps, but certainly no “dragon lady” either.

She was just… Nancy, a self-styled winner who ultimately lost more than she’d ever won. Which even applied to this noxious book, her last-ditch attempt to set the record straight while still accepting as little blame as possible. Here she lost again: squandering this opportunity for genuine reflection, she also gave away the right to insist that she’d never gotten her turn.

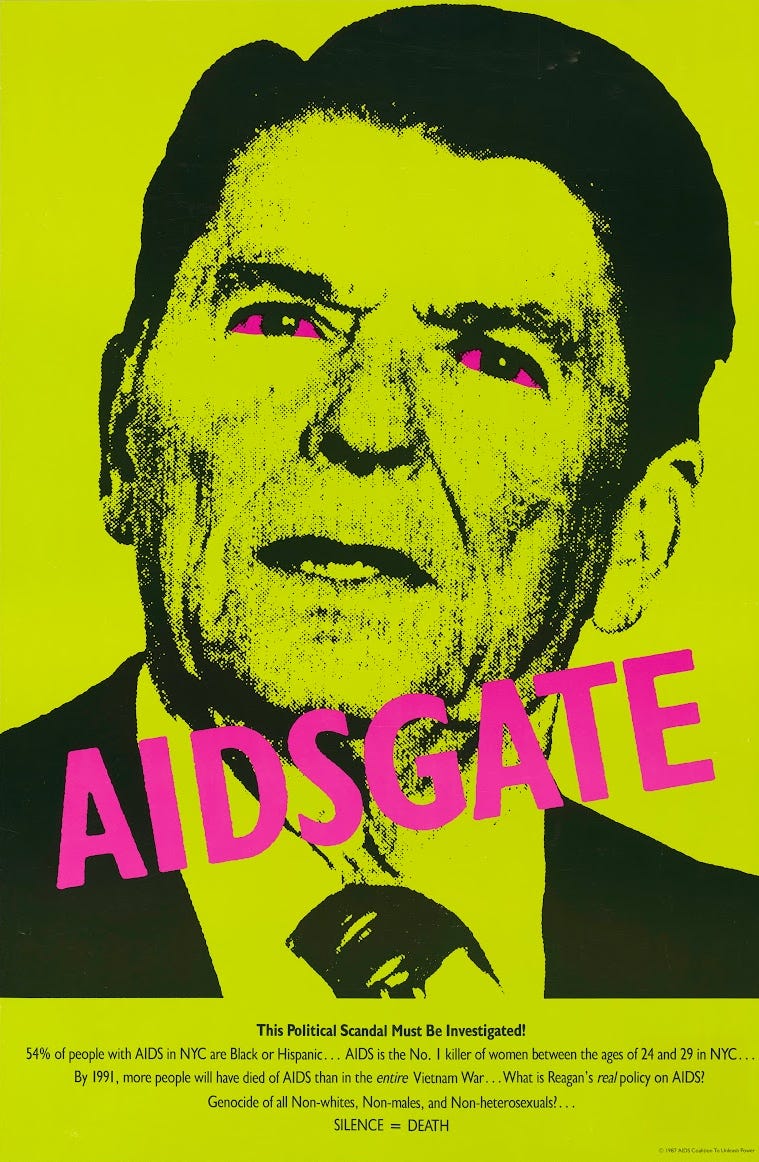

[ACT UP ‘Silence = Death’ protest poster (1987) via Smithsonian archive]

•

If you’ve enjoyed reading this free post, why not subscribe for more JUDGEMENT? Sign up to have free content delivered straight to your inbox, or pay $5 for monthly subscriber-exclusive content! Thank you for enduring this sales pitch.