Lana Del Rey Paints Over Her Bruised Ego in 'Blue Banisters'

T. Bloom recaps the struggle of a new album bearing the twin burdens of accountability and revenge

Chalk it up to astrology if you want (her Cancer is sun, her Leo is moon) but Lana Del Rey is painfully, notoriously sensitive.

This is a desirable, even necessary quality in an artist — one that’s tolerated and even fetishized in brilliant men, whose outbursts of violence are excused as an expression of living with the burden of genius. Last week I watched a show about the making of The Nightmare Before Christmas in which several people recalled Tim Burton angrily kicking a hole through a studio wall in response to the suggestion of an alternate ending. This anecdote was recalled cheerfully (the crew even removed the newly-ventilated section of drywall to have it framed as a memento), as evidence of the director’s cred as an eccentric, passionate creator.

Women auteurs are not only forbidden these kinds of tantrums, they’ve been actively changing the culture and narratives around artistic expression, proving that one can still fight for purity of one’s vision without resorting to tactics of abuse. Although, in the meantime terms such as “attack” or “harm” have grown more vague than ever, making it very tricky to distinguish imminently real forms of violence from more theoretical, philosophical ones.

Without ostensibly ever meaning to, Lana Del Rey has become a lightning rod for this exact form of confusion. Generating a body of work steeped in themes of violence, romance, and femininity, all deliberately presented in a blurry haze that confounds attempts to tell the real from the unreal, Del Rey has become someone who manages to seem all at once very much Of Her Time, ahead of her time, and in some ways, behind the times. The more she swears by the sincerity of her persona and her output, the more repulsive and inexcusable they’re likely to appear… to some. Whereas others protectively cling to their fantasies about her, or even consider Lana’s unsettling “truth” to be evidence of a truly difficult realness — which can be the hallmark of a great artist.

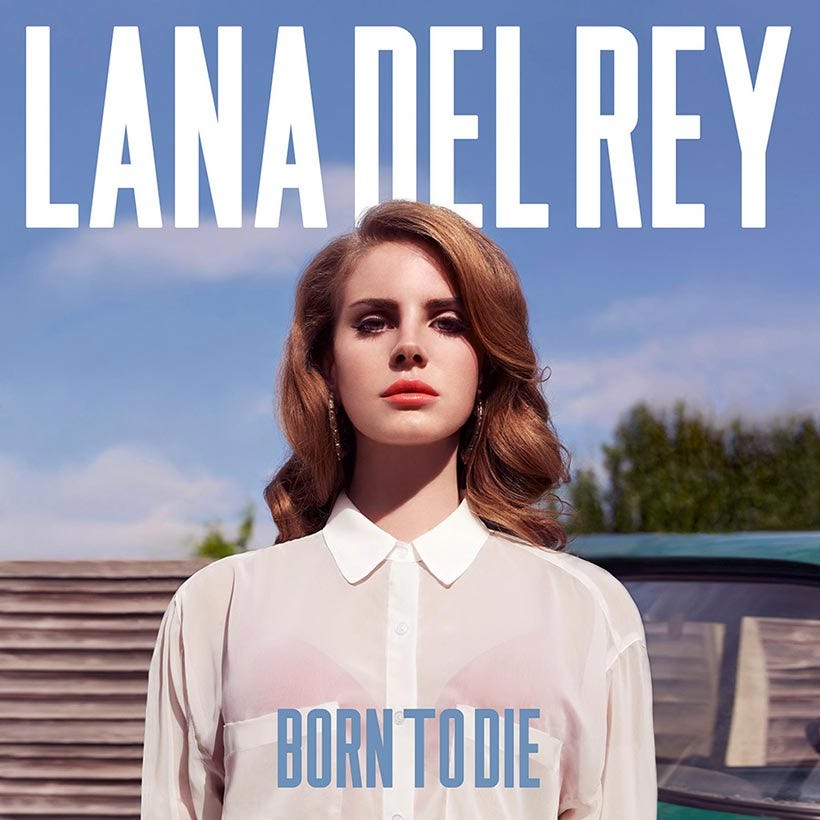

At times this balancing act has pitted the singer/songwriter against the very forces of change she professes to welcome. Her 2012 album Born to Die (recently rescored by Pitchfork, jumping from 5.5 to 7.8) sounded a breathy death-knell for Americana, drafting a revisionist history of the mystical purity of the 1950s and ‘60s, updated with hip-hop influences while not-so-secretly reveling in the desecration and “moral decline” that have made so much of today’s progress possible.

Lana knowingly crafted an image of purity to pair with lyrics that were crass, materialistic, and dirty. The stories she told on these early albums were not just about defilement, but the longing for defilement: the moment of reckoning that occurs when an idealized world collides with a world where ideals are shattered.

But her feints at “empowerment” or whatever have seemed compromised at best. As a voice for women (which it’s not clear she has ever sought to be) her cultural commentary has been regarded as a proper dumpster fire: patently superficial, necrotic, unserious.

From 2016 onward, political realities emerged that Del Rey had no interest and no business participating in; for the most part she’s spent these years openly pining for the bygone eras when artists could shed their inhibitions, living, fucking, and creating in a bubble — as a result, her ongoing fight for artistic purity has always been easily interpreted as laziness, vapidity, and/or privilege. In 2017, lyrics such as “When the world was at war before…We just kept dancing” were meant to offer hope to an already Trump-scarred America, but couldn’t help striking an iffy note amidst a media landscape dominated by urgent, daily calls to action.

And here’s where Lana Del Rey’s vast sensitivity has managed to converge with the aforementioned Tim Burton-esque variety — which is a characterization that I’m convinced is both fair and unfair. Fair, in the sense of Lana’s fragility has become counter-productive to her artistry, frequently inspiring her to lash out at the wrong targets. Unfair, in the sense that her long list of “harms” are definitely of a more theoretical nature, and thus difficult to quantify or atone for. There’s no smashed plaster to show for them, no broken glass, no bruises: just lots of bad vibes, and a lot of beautiful music about making the best of a bad vibe.

While there certainly may be “victims” — of the fans she has “unleashed” on certain critics, of acts of negligence (such as using her social media to amplify Black Lives Matter protest footage, inadvertently exposing participants to greater scrutiny by law enforcement), of her appropriation from other cultures and fellow artists, of her lyrics that “glamorize abuse” — Lana Del Rey’s fits of pique scarcely seem to place her on a scale with more dangerously out-of-control auteurs. But isn’t that standard still slanted toward protecting “edgy” artists who benefit from whiteness?

Those who traffic in symbols are also especially vulnerable to them. By styling herself as a throwback to a bygone era, Lana has exposed herself to all the judgments people are eager to heap upon those who exemplify and long for the past. Lionizing the glamour and artifice associated with womanhood, she’s become someone whose assurances and apologies are not to be trusted. Her attempts to distance herself from her own whiteness can’t help but strike onlookers as the whitest thing someone could possibly do — and her thin-skinned responses to those critics only serve to strengthen their case. Del Rey’s resistance to embracing the expressions and demands of contemporary feminism (the terms of which are not hers to dictate) has transformed her success story into a cautionary tale about white feminism.

The culture may be lit, as it were, but she has decidedly not been having a ball.

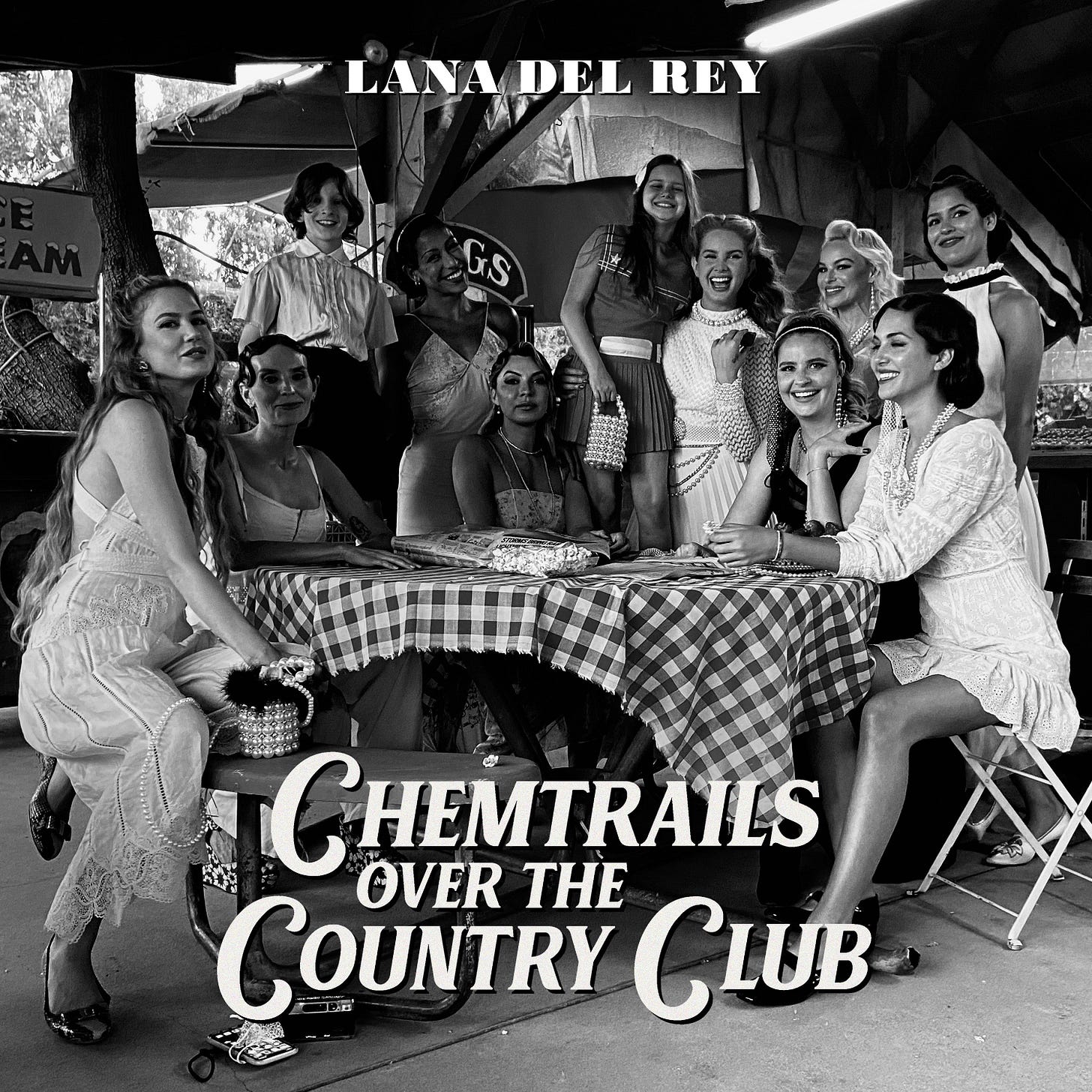

The release of Chemtrails Over the Country Club early this year — Del Rey’s seventh studio album, and her first since the eruption of the coronavirus pandemic — was marked by a flurry of such incidents. For example, the singer swung back hard at a Harper’s Bazaar feature written by Iman Sultan, entitled “Lana Del Rey Can't Qualify Her Way Out of Being Held Accountable.” The article recaps past controversies, presenting them as a consistent pattern in a way that makes some of these missteps seem (in my unasked-for opinion) more deliberate and more nefarious than they really may have been; it also manages to overlook how warmly LDR’s music has been embraced by Spanish-speakers, likely in response to her various shout-outs and references (however dubious) to their culture over the years.

But Sultan’s parting shot hit home:

“Her need to prove that she’s not racist by tokenizing her friends and saying she’s dated rappers…reveals an insecurity about her own authenticity as a white artist, who has always juxtaposed her feminine, all-American glamor with darker-skinned people on the fringes of the American Dream.”

In classic form, Del Rey swallowed the hook with the bait, acknowledging the article in her Instagram stories:

“Just want to thank you again for the kind articles like this one and for reminding me that my career was built on cultural appropriation and glamorizing domestic abuse.

“I will continue to challenge those thoughts on my next record on June 1 titled ‘Rock Candy Sweet’.”

Regarding her “defensive” tone re: race, Lana added: “It would have been unnecessary if no one had significantly criticized everything about the album to begin with…But you did. And I want revenge.”

I think I speak for people of all cultures when I say: oof.

•

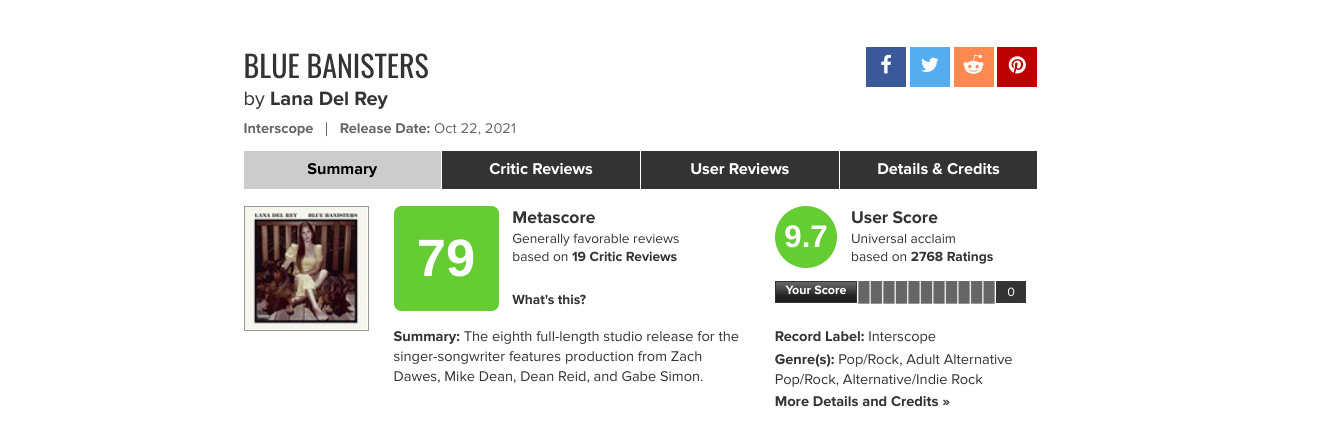

So Rock Candy Sweet became Blue Banisters, and June 1st became July 4th, and then October 22, but an album did eventually arrive. And according to virtually everyone, it was pretty good!

Lana’s claim about the album — that she would use it to challenge thoughts related to her perceived offenses — loomed large in my mind ahead of its release, to the point where I declined to listen closely to the singles released in advance, since the three tease tracks (“Wildflower Wildfire,” “Textbook,” “Blue Banisters”) did not seem geared toward addressing any of this controversy in earnest. I simply refused to believe that Lana herself imagined any of her increasingly impatient detractors would be satisfied by these two lines repeated in the chorus of “Textbook”:

There we were, screamin' "Black Lives Matter" in the crowd

By the Old Man River, and I saw you saw who I am…

It’s not that the lyrics don’t work, or seem insincere. I guess the problem is that they don’t seem to challenge anything. If anything, they reconfigure a public groundswelling moment into a personal one. And while the album overall is far more confessional than Chemtrails, stuffed with vulnerable revelations and casual asides, it was initially hard to detect anything in its contents, lyrically or otherwise, that specifically recalls that unfortunate announcement earlier this year: “I want revenge.”

But, I’ve been reminding myself, but but but… regardless of how “accountable” she has been held, this voluntary restraint really does seem to be a sign of something positive in our problematic heroine. In fact, I’d venture to say that literally everyone involved is better off for it. One could argue that by declining to make art that addresses her detractors, and retreating instead back to her creative bubble world, Lana has successfully fought (herself) for artistic integrity… and against all odds, she’s won.

When you consider her avowed interest in hip-hop, it’s truly remarkable that LDR has resisted temptation to indulge in the rich tradition of diss tracks, rarely naming names or addressing known feuds. This seems revealing of the artist’s relationship with her own art — the need it fulfills, the purpose she intends for it to serve. Despite all these public scuffles, her primary conflict still seems to be an internal one, pitting her devotion to making art against her sensitivity to the way she and said art will be received. This is a classic conundrum, and one that very few women in the music industry have harmoniously navigated, particularly in the social media age.

Whereas the tracks on Chemtrails seemed more remote, filled with escapist sentiments polished to an opaque gloss, there’s a lot happening on Banisters to suggest a shaggy, looser approach to self-revelation, a warts-and-all view of someone (albeit a very privileged someone) enduring many of the same worldly cataclysms as her listeners, with little in the way of certainty about whatever may come next.

“Grenadine quarantine, I like you a lot

It's LA, ‘Hey’ on Zoom, Target parking lot

And if this is the end, I want a boyfriend

Someone to eat ice cream with, and watch television

Or walk home from the mall with

'Cause what I really meant is when I'm being honest

I'm tired of this shit'Cause my body is my temple, my heart is one too

The only thing that still fits me is this black bathing suit…”

Perhaps it’s that very uncertainty which makes Banisters a more enduring work of art: it serves as a necessary crack in the diamond-hard facade that can be so tiresome in works of great beauty composed by beautiful people. There must be a compelling tragedy on display — not just romantic fantasies about suffering, but a real sense of the kind of pain that inspires one to create. That ragged edge is represented vocally by a series of tracks that push Del Rey out of her familiar vocal style, resulting in shouts, wails, whispers, and a particularly husky/throaty register she’s used on occasion, which I can only describe as the sound of someone fighting to hold back tears.

To those less familiar with her work, these differences are unlikely to stand out: her albums are all more alike than they are different, and tracking the stylistic nuances from one album to the next becomes its own form of entertainment to dedicated listeners. Her growth as an artist over the past decade can aptly be described as dramatic… yet there’s still direct continuity to draw between “Video Games” (the breakout single from Born To Die) and her new song “Arcadia,” a torch song in which the the artist transposes her body over a map of Los Angeles, inviting the listener to “run your hands over me like a Land Rover.”

After multiple re-listens, I gradually did discover signs of what I perceive as Del Rey’s “direct” response to all that unpleasantness earlier in the year. Perhaps it was easy to miss because I was searching for something else, based on what I imagined (or hoped) she might say.

Upon reflection, I think those three pre-released tracks actually do constitute the sum of her thoughts on the matter of “accountability,” and her failure/inability to submit to it thus far — especially since each of these are brand new songs, whereas plenty of the other tracks on Banisters were recorded for previous albums.

If these three songs have a unifying theme to them, it’s… brace yourself for a shock… how screwed up she is (a term I relate to and use with love). Del Rey’s obsession with tales of fabulously screwed-up women has been a recurring element from day one, leading her to rhyme “crazy” with “baby” more often than perhaps any songwriter this side of the sixties. Early on, the character sketches in her songs seemed to belong squarely in the fictional world: fantasies about gangsters’ girlfriends, doomed starlets and sex-workers, peppered with literary references to the likes of Nabokov and Sylvia Plath. This contributed to a view of Del Rey’s work as a “synthetic life experience,” instead of a creative expression of her own experiences or concerns.

Not only has the singer/songwriter continued to harbor these interests, over time she’s brought the subject closer to home, alluding more to herself and her personal screwed-up-ness. On Norman Fucking Rockwell she self-identified as “A modern day woman / With a weak constitution / 'Cause I've got / Monsters still under my bed / That I could never fight off.” On Chemtrails she was quick to offer the brightsided rejoinder that “Not all who wander are lost,” but now on Banisters she has finally admitted: “Once I found my way, but now I am lost.”

There’s a kind of double-bind here, for women artists. On one hand, audiences will point to their work (or persona) and say it’s the product of an obviously unhealthy mind. But then if the artist steps forward and acknowledges their personal problems, revealing that they’re indeed unwell, this is viewed as an insincere excuse and/or a bid for further attention. The expectations thrust upon an unwell person are greater, not fewer — especially if they’re part of a marginalized gender or race.

Hence the potential mistake of interacting with Lana Del Rey’s fantasies and statements as those of a manicured, manufactured presence operating from a place of perfect control, instead of a raw, messy, screwed-up artist (her favorite kind). Her lyrical claims to being crazy, disturbed, isolated, irrational, antisocial, etc., are easily dismissed as an artful pose at best, at worst a callous excuse for refusing to engage with the public’s questions and expectations. It becomes tempting to imagine she could do better, grow up, express herself more articulately or transparently, or else — as a last resort — simply retire into obsolescence.

The other issue is fragility, a quality which she has spoken up (inelegantly) to defend. It’s very difficult to disentangle the fragility of her mental states from the type of fragility she openly associates with her gender performance — and which onlookers may associate with her whiteness. The singer’s caveats related to feminism have involved asking for room to be made for expressions of femininity like hers (soft, delicate, fragile, submissive) which have fallen even further out of fashion amidst the great social upheaval of the past decade.

Her clumsiness in broaching these subjects in public is a fascinating contrast to the way she explores them through the lens of songwriting and performance — which is her true superpower, if she could be said to have one. I’m reminded of the mythic figure Antaeus, who was impossible to defeat in wrestling as long as he remained in contact with the earth; Hercules bested him easily, simply by lifting him off the ground. Social media seems to toss Del Rey up in the air, only serving to make her thoughts smaller, lesser.

A more socially adept (or more calculating) public figure might see potential for taking up the cause of “fragility” through disability rights, trans rights, or mental health advocacy; it’s possible to be both white and fragile without courting accusations of white fragility — largely by recognizing the ways in which feminine qualities are additionally exploited and preyed upon in black women, who disproportionately experience sexual harassment and domestic abuse, but also have less access to the services and resources intended to help victims.

But taking up causes isn’t the kind of work everyone can do. Being famous and screwed-up does not qualify someone to join the fight — which is likely the first thing critics would say to Del Rey if she decided to take a more active role in The Issues. And while her heart may (usually) be in the right place, there also seems to be a rueful acknowledgment in Lana’s lyrics that entertaining is literally all she’s good for… and as inadequate as that may seem, given the zeitgeist or whatever, she’s decided to accept it.

Will anyone else?

•

So here are the parts in the aforementioned tease tracks which I think constitute Lana Del Rey’s “challenge” in terms of the cultural appropriation and abuse-glamorizing she’s been accused of.

In addition to her unequivocally repeating “Black Lives Matter” (for whatever that’s worth) in the album-opener “Textbook,” she also very candidly initiates a conversation about her psychological underpinnings, alluding to family hardships which go on to be referenced throughout the album: “I guess you could call it textbook

I was lookin' for the father I wanted back…” Which is a relatively frank way of informing the listener that the “daddy issues” on display throughout all her past works — perhaps most odiously on the Paradise EP, which included the acidic, back-handed Harvey Weinstein tribute “Cola” — are, in fact, her actual daddy issues.

And while such reminders are incomplete as an excuse for bad or erratic behavior, (especially since they’re being presented as artistic fodder instead of a direct statement), they do seem tinged with an air of resignation, as if Del Rey has recognized that she remains incomplete in certain ways, and thus her response to detractors is doomed to be incomplete as well.

Here’s a relevant passage from “Wildflower Wildfire”:

“Here's the deal

'Cause I know you wanna talk about it

Here's the deal

You say there's gaps to fill in, so here

Here's the deal

My father never stepped in

When his wife would rage at me

So I ended up awkward but sweet

Later than hospitals and still on my feet

Comfortably numb but with lithium came poetryAnd baby I, I've been running on star drip

IV's for so long

I wouldn't know how cruel the world was

Hot fire, hot weather, hot coffee, I'm better

So I turn but I learn (it from you, babe)…”

Perhaps I’m overthinking it, but her emphasis on this subject really does seem to constitute an apologia of sorts. The effects of all this background strife are not only evident in the person she’s become (including the way she interacts with criticism) but have also come to define her personal relationships, as well as her public image.

If being accused of tokenism over the diverse array of women appearing with her on the Chemtrails cover struck a nerve, it’s likely due to her genuine dependence — unseen by fans and foes — on a network of close friendships with women. This time, on the title track, she’s careful to add context, putting that sisterhood front and center, singing: “There's a hole that's in my heart all my women try and heal.” Of the ongoing reparative effects of this close contact, she adds: “Now when weather turns to May / All my sisters come to paint…My blue banisters grey.”

All throughout this Blue Period narrative, it sounds like Lana is familiar with feeling like the weakest link in any given chain. Between her ongoing personal psychodrama, the pandemic, and the series of deadly fires (and the persistent threat of more) which have dogged SoCal in recent years, her California experience has hardly lived up to the fantasies she spent so many years spinning. During this time, her litanies of young women enduring fictional crises have steadily given way to the musings of an adult woman withstanding very real ones. The abuses she catalogs belong to her, as do her own problematic reactions to them. Unsurprisingly, the realer she gets about it, the more the critical backlash hits home.

Which brings us to one more major recurring theme in Del Rey’s last few albums — the notion of abandoning fame altogether. For example, in Chemtrails’ “Wild At Heart”:

“What would you do

If I wouldn't sing for them no more?

Like if you heard I was out in the bars drinking Jack and Coke

Goin' crazy for anyone who would listen to my stories, babe?”

While this seems to be an unlikely consequence of all her struggles in the public eye — especially given the admirable performance of Blue Banisters — it does remain as an option she may choose to self-impose, drawing a closer circle around herself and letting her songs do all the talking in years to come. As for now, while “accountability” may be too strong a word to describe this style of address, it’s clear from Banisters that Lana Del Rey aims to harm fewer people, not more.

None of the above is likely to satisfy those who’ve grown accustomed to clear, direct public apologies (the sincerity of which is still almost never beyond question) or the kind of media-savvy appearances that musicians rely on to reframe narratives about their work or past behavior. And it is certainly not my wish to stoke sympathy over the “white women’s tears” exuded by someone who’s picked a few big fights and then retreated behind a veil of avowed fragility. For now, Lana Del Rey has declined to ask for forgiveness, or exact anything resembling revenge. If she has lost fans over the whole mess — as a result of being screwed-up or bad at expressing herself beyond the sphere of her art — that is its own inescapable consequence.

Coping with mockery and poor-faith critiques truly comes with the territory of releasing one’s art to the public, and even emotionally fragile white women need to be prepared for that. However, when engaging with artists and their artwork, critics do need to be better prepared to reckon with individuals who simply do not have their shit together — who may not be mentally healthy enough to engage in serious conversations about broader issues, who struggle to address the public in forms other than art. There are limits to the usefulness of shame when it comes to middling aggressions. That option should be primarily reserved for the worst abusers (who have still proven troublingly resistant to it). And as long as art remains… well, art, we’re going to have to cope with the wide gray expanse of people expressing thoughts or views in ways we consider distasteful or unwise.

This requires us to engage with the idea of harm (or “harm”) as something which may be avoided, but also may not be — from the artist’s side, as well as the audience’s. Problem: there are no clear boundaries for this, and likely never will be. The same could be said for inclusion, or representation, which are important principles that no two projects may achieve (or fail at) in quite the same ways. As we continue to upend the concepts of authority in social settings, prioritizing the involvement of marginalized groups, there will be problems aplenty — avoidable and otherwise — and no one artist, however representative or symbolic they may appear, will be able to satisfy the expectations of the entire public.

We can accept others’ claims of harm, or warnings of potential harm, even if we are personally not harmed or perceive no threat. Still, we often knowingly open ourselves to artistic experiences that we know contain some risk (to ourselves, to others). The elimination of all risk does not create better art; the artist’s struggle, even if it results in a failure, may prove to be a key that unlocks an essential part of our own messy experience. Watching Lana Del Rey walk this tightrope for the past decade, suspended over the gap between intention and execution, has been a breathtaking experience.

As for her cultural legacy (which is no more certain than anyone else’s, nowadays) it seems we can still count on her for a sardonic brand of commentary from behind the shifting veils of privilege, glamour, and success. Since the beginning she’s honed in on the distinctly unsatisfying and unsavory aspects of the world she has inherited through her prodigious combo of talent and image, sincerity and artifice. The last track on Banisters gives it to us with both barrels:

“You name your babe Lilac Heaven

After your iPhone 11

'Crypto forever,' screams your stupid boyfriend

Fuck you, Kevin…”

This nonsense is simply a part of our world now, and Lana is inhaling the vapors from the pit at full blast, a swooning Pythia reporting live from the scene of apocalypse.

Unsavory and unhelpful as her revelations may be, we should think twice before shooting the messenger.

•

If you’ve enjoyed reading this free post, why not subscribe for more JUDGEMENT? Sign up to have free content delivered straight to your inbox, or pay $5 for monthly subscriber-exclusive content! Thank you for enduring this sales pitch.