Justice For Helen Kane, Who Booped and Failed

How the history of a famous cartoon character became rife with racial misconceptions

By T. Bloom

I don't expect to change how the entire internet works by pointing this out, but surely we've all observed how contemporary attitudes can combine with gaps in information, in a way that ends up warping history.

Can it be unwarped? Perhaps, with great effort. Will people thank you for issuing these corrections? Quite rarely. Will they perceive malodorous intentions behind your effort? Very likely… and what’s worse, they may even be right! There’s an unconscious aspect to white fragility which lets us imagine we are serving as noble custodians of history or language, when actually we’re simply addicted to gatekeeping information, preserving the “official” version of the truth.

But historical events don’t exist to teach us a lesson. They are simply things that happened to people, compiled into a catalog of information that is selectively presented in a way that can be used to teach a lesson. Human lives are messy, and the methods for recording important events are miserably inadequate. That’s still as true today as it was a hundred years ago — we can record everything that happens to us, but the sheer glut of recorded information does not automatically lend itself to being searchable, shareable, verifiable, or “complete.”

So, in just a few generations, we’ve gone from folks indulging fringe views about the veracity of historical moon landing footage (produced during a time when special effects were difficult and expensive to create) to an era when people of all ages must remain on the lookout for media manipulation tricks such as “deepfake” technology. Adapting at high speed, we’ve trained ourselves to be instinctively mistrustful — even of HD video footage gathered only yesterday by presumably trustworthy sources.

So what chance does history have? And what part do we end up playing in it by spreading false information, even with the best of intentions?

What follows is not a correction, then, but a plea. I don’t claim to have a pipeline to direct, indisputable sources of information. I cannot build a bulletproof case. I especially do not mean to appear protective of whiteness, and would simply rather know the truth, if it refutes my assumptions. But what follows is not a black-and-white case… or at least, it didn’t start out that way.

I am referring, of course, to that of Helen Kane, who became famous first for her frivolous stage presence (which my boyfriend and I like to characterize as “miserable woman baby”), and then again later as a litigant when her likeness and vocal affectations were ripped off and adapted into the cartoon sensation that became known as Betty Boop.

There are two main types of conversation about this online. The first tends to revolve around trivia naming Kane as the “inspiration for Betty Boop,” usually citing her failed 1932 lawsuit against Fleischer Studios.

The second tends to namecheck Kane as just a stepping stone in the troubled Boop legacy, branding her as a “white imitator” who stole the act from a certain Esther Lee Jones, aka “Baby Esther” — a less famous Harlem performer who allegedly also sang in boops and doops. These trivia nuggets are often presented in meme form, or written about in modern terms like appropriation. In which case, Kane is presented as a blandly pernicious figure who had the gall to steal a Black performer’s act, and then sue someone else when it was swiped from her.

Reader, I ask you to remain open to the idea that history may just be one long lineage of miserable woman babies. We truly shall never know.

Esther Lee Jones, aka “Baby Esther” (1930)

I come not to exonerate Helen from stealing Esther’s act, but to shine a light on everything that is missing from this oft-repeated narrative. Framing Esther as a victim of Kane’s — instead of as yet another victim of Fleischer Studios, who successfully (and cynically) invoked Esther in their defense against Kane — pits the legacies of these two performers against each other, when actually, as women in a male-dominated business, they faced the same common enemy. This is a numbingly common tactic in presenting stories about women, historical or otherwise.

Also, the incomplete version of these events is a less interesting story overall, although I admit it sure makes for a helluva meme.

Indeed, the waters around this particular case (which traveled all the way to New York’s Supreme Court) are so muddied that someone wading out into them almost a century later can see pretty much whatever they want to. That, by the way, is the intended result of oppression and erasure; it makes the status quo look simple and cleaner in comparison. Most won’t necessarily think to go looking for that which has been made invisible, and those who do the work of reclaiming history are accused of trying to “rewrite” it.

It’s safe to assume racism is usually involved somehow, although it still remains possible to leap to the wrong conclusions due to the "right" reasons. Historical moments are often more complex than they appear, and there’s a difference between “doing the work” of research/reclamation vs. filling in the blanks with assumptions that create an alternate (false) history.

[Neither Baby Esther or Helen Kane are pictured in the above example]

I can’t write about the entire court case in the detail it deserves, but here are a few basics:

By 1930, Helen Kane had become a Broadway sensation and film starlet, after a decade spent building up a career in vaudeville and musical theater. By the accounts I’ve read (which again, lol) she had nowhere left to go but down; obviously the baby-singing schtick was not gonna age well, but she was certainly making the most of it.

Then in 1932, Fleischer Studios fully converted the crudely-drawn chanteuse introduced in their “Dizzy Dishes” cartoon (an obvious Kane caricature, and perhaps predicting the appeal of Snapchat’s dog filter) into the neotenous humanoid icon known as Betty Boop, who became an instant sensation. As an animated songstress, she could appear and entertain in cities all over the country, for the price of a movie ticket. What flesh-and-blood performer could compete with that?

Kane sued them for $250K (equivalent to almost $5M today), accusing the studio of exploiting her image, personality, and vocal performance. Most of the court records that have drifted onto the internet revolve around Boop’s “boops” — perhaps because this part of the case was so much fun to report on.

But here’s where it gets tangled: Fleischer Studios appear to have pulled every bullshit trick in the book in terms of their defense, which rested on disproving Kane’s claim to the originality of her performance.

Now listen. We’ll get into those details shortly, but it’s worth underscoring: they did, in fact, knowingly base their character on Helen Kane, cashing in on her fame. But however valid her case, there’s no way a baby-voiced Jewish woman from the Bronx with roots in vaudeville was likely to have her claims against male plaintiffs taken seriously in a courtroom filled with men, and reported on by men. Helen Kane’s failure in court does not negate the legitimacy of her claim, nor does it validate any of their counter-claims against her.

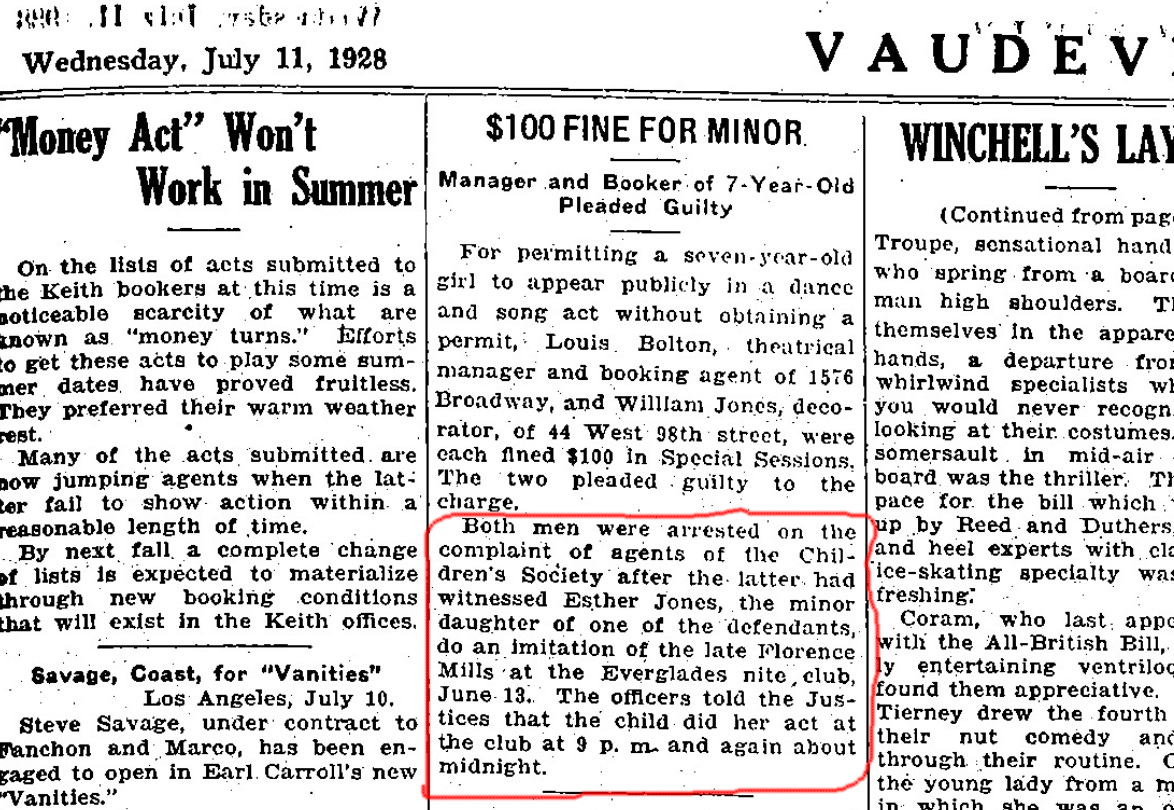

One of the defense witnesses most cited by those rehashing the case today was Lou Bolton, a theatrical manager who claimed he’d personally seen Kane at one of Baby Esther’s shows — although under cross-examination, he also admitted the Fleischers had paid him $200 to testify. I find it shocking that today his testimony is widely accepted at face value.

The Fleischers came to court armed with examples drawn from every miserable woman baby in the biz, comparing Kane to numerous other singers and casting such a wide net that they even cited a French song from 1915 called “Bou-Dou-Ba-Da-Bouh” (which is the name of a Senegalese character described in the lyrics).

It seems the case was treated as a joke by pretty much everyone except Helen; according to History.com, following her loss “a vindictive Max Fleischer even gathered his Betty Boop voice actors on camera to make fun of the lawsuit during a newsreel — and not long after, Boop herself appeared in a cartoon called ‘Betty Boop’s Trial.’”

So look, Kane herself served as a historical example of just how many ways they can screw you. There’s nothing in this story that makes her a figure worthy of contempt or ridicule today. She was simply a woman who worked hard for many years, enjoyed an surprising amount of success, and grew just big enough to steal from. The Fleischers were cultural opportunists who saw a chance to grab something valuable for free, and ran with it. They did not see a woman like Kane as an artist worthy of respect; to view her image or performance as intellectual property, they would have first needed to imagine she was capable of intelligence (which, likely owing to the campy, childish nature of her stage persona, they did not). So instead they considered it fair game to exaggerate her body and mannerisms, further sexualizing her and infantilizing her, making her into their extremely profitable puppet.

And when called out, they not only insisted upon their innocence, they made a mockery of her claims and used them to further popularize their glittering new product, Betty Boop. They even cynically presented another woman as the real victim — Helen’s — without acknowledging that, by extension, that implied they had ripped Esther off as well.

(These were, and still are, perfectly normal ways for powerful men in showbiz to behave.)

Now let’s dig a little bit further into Baby Esther, whom the Internet has retrofitted as “The Original Betty Boop.”

I refuse to make a call either way on whether Kane saw Esther’s act, or knowingly imitated it; the facts simply aren’t there. But let’s assume she did see it!

There are no confirmed recordings of Esther singing, so a direct comparison isn’t possible. It’s hard to tell, but it seems the Fleischers’ claims re: Esther related purely to the “scat” style of singing which they connected to Kane’s “Boop boop-a-doop” vocalizations, though even today Esther’s wiki page describes her pet versions of the phrase as "boo-boo-boo" and "doo-doo-doo.”

In court, the defense presented a recording of Esther singing three songs which had been earlier popularized by… Helen Kane. The origins of that recording remain unclear, and it’s difficult to tell what (if anything) could possibly have been clearly deduced by this evidence at the time. Notably, Esther herself did not testify or offer comment, though she had returned from a world tour and was in the United States by that time.

The squeaky-voiced schtick was certainly not original, but I don’t think Kane ever claimed as much. It was, in fact, simply part of the flapper trend; in 1929, The New York Times referred to Kane “the most menacing of the baby-talk ladies,” naming a few others in her league. She simply happened to be the one whom the Fleischers had decided to clone.

So let’s say Helen Kane saw Baby Esther’s show on that fateful night in 1928. While exact date of Esther’s birth isn’t known, best guesses suggest she was around ten years old, perhaps younger. As a more worldly woman batting in a different league, would Kane have considered a literal child to be her artistic peer? Might she have felt a little more license to adapt some minor element from a kid’s routine into her schtick, which involved… acting like a kid?

Especially since, according to a Variety article from that time, Esther’s act was itself billed as an imitation, of Florence Mills — another famous Black singer at that time?

Could this have affected Kane’s perception of the originality and accessibility of Esther’s routine? As a standout in a field replete with grown baby-ladies, did Helen knowingly become a woman imitating a child who was imitating… another grown woman?

And if so, I ask you: is there any real justice or empowerment for Esther in being known as “The Original Betty Boop”? She never claimed to be so — despite having been afforded ample opportunity to. If a fragment of Esther has lived on in Betty Boop (though again, there seems to be no concrete proof of this, except that which was provided by a bribed witness), then it is definitely worth acknowledging. But then, is anything owed to Florence Mills? Did she ever boop, even once?

Because that is the sum total of Helen Kane’s alleged appropriation. Not her appearance, nor her vocal style (again, she’d been a well-known singer for years before becoming a recording star), but that little bit of booping introduced in her hit song “I Wanna Be Loved By You,” recorded in 1928 — a song which, mind you, she did not write. (It’s credited to Herbert Stothart and Harry Ruby.)

I don’t intend these questions as a gotcha! to any who have embraced the idea of Betty Boop’s blackness, nor do I wish to reinforce the attitude of defensive whiteness that automatically looks askance at every claim of appropriation. Reclamation is powerful, and urgently needed; it’s a safe bet to assume there is some degree of white supremacy and Black erasure involved in every aspect of our history. Urgency, however, may lead to errors, and the Internet is a medium that affords error plenty of room to flourish and take root, until it becomes a sort of parallel truth.

The Fleischers did, however, wield Baby Esther against Helen Kane as a gotcha!, and won. And as people say, history is written by the winners.

If Kane did, in fact, appropriate her “boops” from Esther, it was an extremely fateful decision, and one she paid dearly for in court, as well as in the public eye, all the way to the present day.

But based on what is known, I would argue there has never been any such thing as an “original” Betty Boop. It certainly does no service to Helen Kane’s memory to be remembered as such, since she was already quite well established as herself: Helen Kane. Nor was Baby Esther the original Betty Boop — she was an artist in her own right, who traveled the world and enjoyed her own modest amount of renown and perhaps accidentally contributed to a small aspect of a famous cartoon character, a composite portrait of rip-offs that just happened to strike gold.

There is Blackness in Betty Boop, absolutely — not just because of Esther’s rumored influence, but because of how the Fleischers’ cartoons were used to popularize music by jazz singers such as Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong. As History.com’s article points out, “Boop’s cartoons help preserve America’s long-gone vaudeville tradition—one that was based, in large part, on the contributions of unacknowledged African-American performers.”

So a cultural debt is owed, for sure. I’m simply not convinced that Kane is the one who owes it, or deserves to be stripped of her own modest cultural contributions, going down in history as a rank imitator when she was among those who suffered from being unfairly imitated.

Over the past decades, even before folks began re-exploring her connection to Esther, Boop iconography had already been adopted by Black and Latinx culture, seamlessly making the transition from jazz-age baby to gangsta-rap baby. Her racial ambiguity and innocent brand of sex appeal dovetails neatly with the rebellion against contemporary measures to police young Black women’s bodies and sexuality. Boop offers a historical tether to the concept of the “bad bitch” who is clearly just out there enjoying her life, causing comment and provoking lust simply by existing, but is a still a decent and loving woman at heart.

Overall, I would much rather people demonstrate an interest in correcting historical erasure than continue to perpetuate it, even if important details end up being left behind or overwritten. I certainly do not view the Internet’s retooled narratives about Baby Esther as a form of “erasure” on par with what Black artists have experienced (and still experience), and it brings me little satisfaction to attempt to correct them, knowing how misinterpreted that gesture may be.

Hopefully the takeaway here is simply that “Helen vs. Esther” is an imaginary battle, one which has become emblematic of the very real war being waged against white supremacy in pursuit of Black recognition. And if Esther has ended up becoming more famous for this than she really ought to have, it’s at least served as a way of preserving her memory and drawing attention to her more legitimate contributions, even if there’s no way to hear her voice.

As for Kane, I really enjoy listening to her music. It’s not Betty Boop’s double-wide noggin I’m envisioning when I hear her whimpering through songs like “Dangerous Nan McGrew,” even though most compilations of her work still bear Boop’s image. I relate strongly to the idea of the miserable woman baby — someone who has all the assets which are supposed to make them irresistible, and yet, more often than not, still ends up singing about being left unsatisfied.

But despite everything, I’m sure Helen would agree: ‘tis better to have booped and lost, than never booped at all.

[Comments are not enabled on JUDGEMENT posts. If you have questions or comments, you may send them to judgementnewsletter@gmail.com]